20201006澳大利亚政治人物家庭遭受邪教伤害(1)

中文

全文可用。虽已全和法无关,但内容具有代表性,全文翻译近7000字,质量较高,建议以一篇发布,计入合同篇目。WLF

澳政治人士自述家庭悲剧:我的妻子“死”于邪教

Gavin Butler 王研(编译)

核心提示:美国VICE新闻网(vice.com)2020年8月20日发表高级记者加文·巴特勒(Gavin Butler)的深度报道,澳大利亚政治人士内森接受采访,讲述了自己的亲身经历,回忆妻子凯莉是如何被一个狂热的膜拜团体拉拢并“驱魔”的,文中反思了什么样的人容易陷入这类团体。内森坦承,澳大利亚现有法律难以保护民众不受邪教侵蚀。中国反邪教网全文翻译如下。

一

一个以基督教为名的狂热膜拜团体把内森(Nathan)的妻子变成了幽灵附体的陌生人。他正在为保护其他人免受类似遭遇而战。

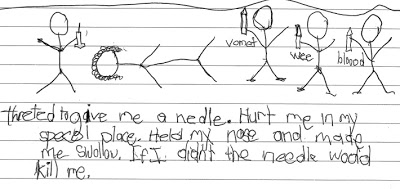

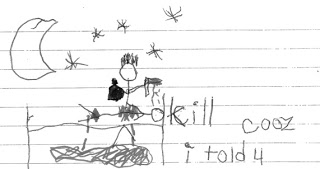

2015年,内森在当地集市上发现了一幅凯莉的画像,他觉得“很奇怪”。原文配图

“我会按指示杀人。我是撒旦的小婊子。”2009年6月6日,内森的妻子凯莉在一张日历便签纸上这样写道。而在五个月零两天前,凯莉开着借来的房车去参加一个圣经学习小组,后再也没有回来过。内森认出这是凯莉的笔迹:熟悉的,而又潦草得一塌糊涂。他曾把凯莉当成自己的灵魂伴侣。在凯莉离开他和儿子12个月后,从许多忏悔信上,他又看到了这样的笔迹。

“如果不服从,就会死。”另一张便签上写着:“我是个坏女孩,我活该……我很丑,我什么都不是。教会最重要。”

内森清楚地记得那个下午,凯莉正准备参加妇女圣经学习会,出门前她说会回家吃晚饭。凯莉与悉尼西部蓝山下麓一小群基督教徒建立了友谊,此后,她开始定期参加这个学习会。

内森由衷地为凯莉感到高兴。六年前,他们的儿子利亚姆(Liam)出生后,凯莉经历了几次短暂但严重的产后抑郁症。现在,看到她与一群看起来仁厚亲切而又志同道合的人交往,内森真是松了一口气。

其他小条上的字他都不认识。内森猜测很可能是这个小组其他成员草草写下的,或者可能出自凯莉的多重人格之手,据说她的多重人格现在多达数百。

失踪前几周,凯莉开始参加“咨询会”。一些纸条似乎是那时匆匆写下的。许多看起来像是孩子潦草的字迹,婴儿版凯莉的手迹,描述了遭受严重折磨和虐待的场景:挂在树上的狗;被砍了头的婴儿;男人们被砍掉舌头,嘴巴钉死,眼睛用火棍烧瞎。

十年前,一个名叫韦恩的男子将这些信件和便条转交给内森,他的妻子也因这个团体失踪。韦恩当时告诉他:“妻子离开之前我收集了这些东西,都是关于那座房子的谎言。”“我不敢相信,但她们什么都记着。”

韦恩收集的便条读起来像是来自另一个世界:一个由天使、魔鬼和基督教神话组成的世界,据说都发生在内森的眼皮底下,在蓝山下麓绿荫丛生的郊区。这是一个女人如何沦为狂热膜拜团体牺牲品的例子,也是了解好人如何被邪恶教派吸引的难得机会。

更重要的是,它们是一系列超现实事件的亲笔证词。曾经很长一段时间,内森认为“这是发生在别人身上、电影里,或电视上的事情”,但现在他已经接受了这是真实的,这事就发生在自己身上。

二

2009年以前,内森和凯莉夫妇的生活平淡无奇,内森自己也这样认为。

那时他们刚搬到蓝山山麓附近的一个小镇:这是世界上最安静的地方,以其迷人的乡村社区、引人入胜的自然风光和外人半讥半讽的“邪教”闻名。他们拥有一座房子,都在同一所跨教派的基督教学校工作,内森在I.T.部门工作,凯莉则是一名前台接待员,每天早上,他们开车送6岁的儿子去幼儿园。在内森眼中,那是“美好的生活”。

内森一家三口。原文配图

“我们的婚姻和家庭生活非常典型。这是一个传统的家庭,如此平凡,但又如此幸运,”内森在视频通话中告诉VICE。随后说出的这句话多年来反复提及:“恐怖的故事通常从一个普通的场景开始,然后逐渐变得邪恶。我们的经历正是如此。”

事后复盘,很容易看出邪恶势力是如何一步步进入内森家的。凯莉的梦想是在悉尼一家大医院做急诊护士,不过在身体完全康复之前,她先是到这个跨教派的基督教学校临时代班。最严重的抑郁症似乎已经过去了,凯莉开始尝试着与他人交朋友,不久,一个和学校董事会密切相关的团体邀请她参加每周的圣经小组学习。

内森说:“那正是麻烦的开始。现在我恨死自己(当时没有在意)。”“没有人会说‘嘿,加入我们的队伍,我们将会毁了你的生活’,没人会这样拉你入教,但当时我并不知道(这是一个邪教)。她偶尔晚上出去和这帮人来往。”

渐渐地,这样“奇怪的夜晚”变得越来越频繁。后来,她们跑了。内森不止一次回忆起,多少个午夜他在等待凯莉回复信息。他开始注意到妻子的变化,担心她的抑郁症会再次席卷重来。更多的时候,是另一个叫维吉尼亚的女人回复的信息:凯莉正在接受心理咨询,早上会给他回电。

2009年1月5日早上,凯莉没有打电话,也没有回家。从那以后,她再也没有回家。

三

内森衬衫扣子整齐,表情柔和,外表和蔼可亲,但又固执无情;既彬彬有礼,又直言不讳;既自信不疑,又昼警夕惕。他把自己描述成一个颇有经验的品行判断者,一个乐观主义者,一个经验主义者,一个不确定上帝是否存在主义者。

他说:“我看到了足够多以耶稣之名所做的邪恶伪善之事,多到够我这辈子回味。”“基督教徒把我拒之门外。”

2010年,内森加入了“邪教信息与家庭支持组织”(Cult Information and Family Support group,CIFS)委员会,该组织是澳大利亚重要的邪教虐待宣传网站。他为那些因邪教失去亲人的人提供咨询,或者给那些从邪教中走出来,需要处理过往经历的人提供帮助。

“人们对邪教的反应各有不同,”他说。“有些人从邪教中走出来后,会自闭,而有些人为自己多年被剥夺了正常生活或人际关系感到愤怒,他们会保持善良和愤怒。”

“我也住在那个营地,但很奇怪,我从来没有参加过这个邪教团体。失去爱人令我怒不可遏。”

直到凯莉离开一年多后,内森才知道圣经学习会上真正发生了什么:维吉尼亚的丈夫韦恩递给他一摞笔记、涂鸦和恶魔般的胡言乱语,记录了这整件事。

“她们是在这里见面的,”内森和韦恩第一次碰面,是在韦恩家的餐厅里。韦恩指了指门窗上的一堆污迹,告诉他:“你看到那些油腻的痕迹了吗,内森?那是他们用圣油做的小十字架记号,是为了把恶魔挡在外面。”

韦恩接着解释说,这个团队一直在为凯莉“治疗”,诊断她患有一种被称为“分离性身份障碍”(以前称为多重人格障碍)的疾病。“分离性身份障碍”是指个体的心理分裂成许多不同的人格或“替身”,通常用以应对童年时期所遭受的创伤。她们坚信,凯莉小时候经常发生撒旦仪式虐待事件,由此造成这种创伤。

治疗过程,她们鼓励凯莉回忆家人虐待自己的可怕记忆,陈述的一些指控包括:被迫住在房子最底部,像狗一样被喂食;耳朵被灌入开水;包着头巾的人将她带到丛林见证人类的牺牲。

内森表示:“所有这些说法都非常非常疯狂。”“凯莉是四个兄弟姐妹中最大的,据说她的成长经历完全正常,家庭充满爱心。”

凯莉写的便条。原文配图

不过,对维吉尼亚和其他人来说,这正好说得过去:在这么小的年纪,经历这种极其残忍的虐待,恰恰是引发创伤的主要原因。在她们看来,凯莉的思想已经分裂成数百个“人格”,以此来逃避她痛苦的过去。有些人格天真又孩子气,被冠以类似“希望”“开心”和“真实”之名,有些则被视为恶魔,起名诸如“黑暗”等。

维吉尼亚说:“有些人格想要伤害她。”“这些人格会去喝漂白剂,会试图把她的手放在火里,会跑到卡车前面。所以我们必须把门锁上,以确保她的安全。”

大多数人可能会认为这是严重心理问题产生的行为,这个团体则认为是撒旦在作怪。除了锁门关窗,她们相信只有一种方法可以解决这个问题。

“所以,她们对凯莉进行驱魔,”内森说。“这样的事情发生在二十一世纪的澳大利亚……她真的患有精神疾病,但她们却诊断她身上有恶魔,要把这些恶魔赶出去。”

凯莉的涂鸦。原文配图

就在这个时候,内森收到凯莉的一些信件,内容令人不安,其中一封是写给儿子的遗书。同一时期日记中的某些涂鸦也曾作出类似不祥的声明。其中一张便条上写道:“我将不惜一切代价服从。”另一张上面写着:“唯一的出路就是死亡。”

四

内森最后一次见到凯莉是在五年前。他清楚地记得她当时的模样:“身体不好,弱不禁风,一副完全受邪教控制的样子。”

据他所知,凯莉在认识维吉尼亚等人之前,从来没有患上“分离性身份障碍”,尽管他承认,凯莉有时会说一些“无稽之谈”,通常也是在社交场合为了讨好别人或引起他人注意。总的来说,他坚持认为,和其他人相比,她没缘由更易受到操控或教化皈依。“那不是跟我结婚的人,”他说。“根本不是。”

言外之意,这可能发生在任何人身上:在一系列特定的不幸事件下,毫不起眼的普通人可能会转而陷入最不可能发生的漩涡中。很难回避这样一个问题:对一个人你到底了解多少?从表面上看,所谓施虐者的腐败、操纵和激进主义进程,在多大程度上代表了所谓受害者自觉自愿的行动?

换而言之:当一个人背井离乡,离开生他养他的家庭,加入一个宗教派别时,他受到影响的可能性有多大?在凯莉的案子里,内森指出大约是50%。

“为什么有人会卷入邪教?”他沉思着。“人们参与邪教是因为他们愚蠢吗?显然不是。有些非常聪明的人也会陷入其中。那到底是什么?我们要找的特征是什么?”

解决这个问题花了内森很多时间。他认为答案是,一个人在某种情况下的脆弱性。比如他们最近搬到了一个新的城市,或者没有新的朋友,也许他们正处于“寻找生命终极答案的时期”。内森说,这正是邪教徒们伺机而入之机。

“我同情我的前妻,”他告诉VICE。“她除了做出一些特别糟糕的选择,这点不是很妥外,我不会把她描绘成故事中的恶棍进一步伤害她。她是受害者,而真正的坏人是邪教。”

五

这个故事既老套又普遍:一只披着羊皮的狼引诱一个脆弱的教徒加入一个伪精神团体。在与其他有类似经历的人会面交谈后,内森意识到,他的妻子被这个团体拉拢的方法绝大多数来自于《如何招募邪教成员》(How to Recruit Cult Members)这一剧本。

他解释说,这类组织通常会采用一些技术手法。首先在他们心中播下种子。团体中的一个或几个成员会巧妙地说服那个脆弱的个体,说他是特殊的,有独特的命运正在等待他实现,亲朋好友正阻碍着他前进的道路,可以通过另一条途径完成最大程度的自我实现或自我启蒙。通常情况下,达到这种状态的路途遥不可及,这促使个人为团体投入更多的人力或财力,以尽量实现圆满。

于是,皈依者被迫相信他们应该无视他人的意见和建议,尤其是当这些意见和建议批评的是自己所在的特定教派团体。他们渐渐摆脱了家人朋友情感的羁绊,慢慢拥有了他们的“批判性思维工具”——当事情不太对劲时,大脑中可能会响起警报。

内森解释说:“那些对你我来说显然是不可能的事情,对邪教成员而言却很有可能,因为他们的部分大脑已经被麻醉了。”“人们能够从邪教中走出来,往往是因为他们的批判性思维能力又恢复了。当他们意识到自己被虐待,于是就离开了。”

但凯莉没有机会走出来。相反,这个团体逐步收紧了对她的控制,争取志同道合信徒的帮助,对她进行“分离性身份障碍”诊断,并试图夺取她的法律监护权。最终政府判定凯莉确实身有残疾,不适合工作。维吉尼亚现在是她的监护人。

内森觉得凯莉和维吉尼亚都陷入了一种共同的妄想症,或者叫“两个人的疯狂”。他说,让凯莉生病符合维吉尼亚的利益,维吉尼亚甚至可能会加重凯莉的症状,以便她能够扮演看护者的角色。

这种现象有个名字。当看护者捏造、夸大或导致受其照管的人生病或受伤时,临床医生称之为“孟乔森症候群”(译注:Munchausen,这种患者会伪装或制造自身的疾病来赢得同情照顾或控制他人),通常原因不明。孟乔森症候群被广泛认为是一种精神虐待。但内森后来发现,在凯莉和维吉尼亚的案例中,这种安排也存在经济利益。

他说:“据我所知,过去十年里,她们都没有从工资中提取一分钱,因为她们获得了政府福利。”“一个是需要照顾的残疾人,另一个是专职护理人员,她们靠这个收入过日子。”

这场互相折磨的关系得到了合理化解释。但她们遭受了这么多痛苦,这个教派团体从中又得到了什么?

“提到邪教或邪教头目,人们经常问的问题是:他们是疯了还是病了?”内森解释道。“换言之,他们是在欺骗,他们知道这一切都是骗局;或者他们被欺骗了,实际上他们相信自己是教会余下来的那些忠实信徒,主流宗教派别都正被魔鬼崇拜者秘密控制,他们不时地在偏僻的地方聚集献祭。”

他总结说,凯莉所在的这个团体属于后者。

“他们确实相信这些东西。对他们来说,这是一种认可,是一种对他们特定的精神神学信仰的辩护。他们相信自己正在与一个在蓝山上活动的撒旦教徒进行精神上的斗争。你可以指出来,笑话它,但你必须明白:这不只是荒谬的,还是危险的。人们正在受到伤害。”

正因如此,内森和“邪教信息与家庭支持组织”一直在呼吁澳大利亚政府,通过加强对行为而非信仰的限制,来打击邪教的拉人行为。

“只要你愿意,你可以相信月亮是奶酪做的,”他解释道,“但是如果你开始在精神上虐待他人,扰乱他们的心理,榨干他们的银行账户,让他们断绝与家人的感情联系,那就是一种暴力行为,应该得到惩治。”

事实证明并非如此。尽管澳大利亚法律明确禁止绑架、欺诈和强行拘禁他人的行为,但并没有法律禁止洗脑、恐吓或胁迫行为。内森和“邪教信息与家庭支持组织”认为,这些构成了心理虐待,但对于心理虐待还没有明确的立法。这类心理虐待导致犯罪行为结果之间的关联,很难证明,更难查清。

维多利亚迪肯大学(Victoria's Deakin University)刑法学博士保罗·麦戈瑞(Paul McGorrey)通过电子邮件告诉VICE:“迄今为止,在澳大利亚,没有一个人因实际对他人造成心理伤害而被起诉。”“据我所知,跟踪法从来没有像你描述的那样针对心理虐待实施过,我们也没有将心理虐待定为犯罪的专门法律。”

简而言之,澳大利亚法律保护人们免受邪教掠夺的最好办法就是各种各样的稻草人和纸老虎(译注:指代法律毫无用处)。

这就是内森,一个自诩为乐观主义者、经验主义者和不确定上帝是否存在主义者。这也是内森·赞普罗格诺(音译,Zamprogno)作为一名政治家的新生活,正在为之奋斗的方向。内森在2016年当选霍克斯伯里市议会议员,并在2018年代表自由党预选新南威尔士州霍克斯伯里市议席。现在他希望各国政府围绕宗教自由,通过切实有效的法律,起诉那些给他人造成心理伤害的人。

他解释说:“一粒老鼠屎坏了一锅粥。”他希望看到澳大利亚慈善机构、非营利性委员会和税务局等机构实施更为严格的公益测试,并成立一个正式机构,对激进宗教团体进行严格审查。

将自己的妻子从这个危险的团体中拯救出来,内森早就放弃了这一念头,但这样的努力探索已经融入了他的公共生活。

他说:“我不再为凯莉而战。事情发生三四年后,我允许自己安于现有的生活方式。”“从她失踪的那一刻起,我就乐此不疲地想要把她从邪恶的处境中解救出来。但我渐渐意识到,用伏尔泰的话说,‘将愚人从他们所敬拜的锁链下解放出来是非常困难的’。最终,不得不放弃。”

六

内森和他现年18岁的儿子利亚姆住在悉尼西部的霍克斯伯里地区,从那里可以远眺蓝山。利亚姆现在已经上12年级了,内森在自己和凯莉两家人的帮助下,以单亲身份抚养他。内森承认自己现在生活得很好很开心。

自从凯莉开车离去十一年半后,内森重新找回了他曾经珍视的那种愉快又偶生嫌隙的传统生活。他懂得了平凡的生活并不能阻隔不寻常的事件;信仰与善良或美德是不一样的;而奉献,特别是极端的奉献,可以被视为善与恶力量的角力。

有了极端和荒谬的经历,内森艰难地接受这些教训。但任何人如果仅仅觉得他的故事令人难以想象,就都没有抓住重点。

“看看琼斯镇、天堂之门、韦科镇这些邪教发生的惨案,你会问:是什么把人们带到狂热的地步,是什么把他们的信仰变成了妄想?”他说。“作为一个社会,普通人被诱导至此,是一件非常不舒服的事情。同样的道德辩论还包括,为什么好人允许纳粹把人送进毒气室?”

“普通人也会做出非常糟糕的事情。”他总结道:“正如克里斯托弗·希钦斯(Christopher Hitchens)常说的,宗教让好人做坏事,却还以为自己是在做好事。”

维吉尼亚和她的姐妹们从此消失在木屋里。内森怀疑正是他长期的曝光行动,摧毁了该组织在社区中的形象,迫使她们转入地下。但他也担心会有更多的暴行发生。

他预言:“总有一天,这群人会严重虐待别人,不管是凯莉还是其他人,甚至有人会因此受到伤害或导致死亡。”“如果要进行死因调查,得到的信息必是他们难辞其咎。”

至于他目前对凯莉的感情,内森提到了“怜悯”,就是“怜悯,就像有人可能会同情一个人,他在生活中受到了很坏的待遇,或做出了糟糕的人生选择,现在正在饱尝后果”。除了怜悯,没有别的。

他说,利亚姆对他的母亲完全漠不关心,她现在已经只是一个模糊的记忆。利亚姆十几岁时,内森将所发生的一切真相告诉了他。内森一辈子都在保护他,最后把这些一手资料交给了儿子。

“他看了所有的资料,”内森说。“在儿子看来,是那些教派人士偷走了他的母亲。所以现在他不想和组织森严的宗教有任何关系,因为这样的教派会让他想起母亲的一切。”

他们俩早已开始了自己的生活,但这并不意味着内森完全将这件事抛之脑后。

他解释说:“我把这件事定性为人员失踪案件。从某种意义上说,如果一个人死了,事情就有了了结,但如果一个人失踪,那么你甚至连等到结局的机会都没有。”“某个人带着那个人的面容出现,但却不再使用那个人的名字。他只是套着那个人的壳。真是一场人间悲剧。”

他继续说:“我不想在发现真相之前就进行‘死因’调查。多年来,我提了很多问题,可能永远也不会有答案,但我已与这些问题达成和解。为什么这些人会这么做?为什么凯莉选择做这些事?这一切什么时候是个头?我不知道。”

作者:加文·巴特勒(Gavin Butler),VICE亚太区副总裁、高级记者

原文网址:https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/3azyav/i-lost-my-wife-to-a-cult

英文

A PORTRAIT OF KYLIE THAT NATHAN FOUND, "BIZARRELY", AT HIS LOCAL FAIR IN 2015.

I Lost My Wife to a Cult

Christian fundamentalists turned Nathan's wife into a haunted stranger. Now he's fighting to protect others from a similar fate.

By Gavin Butler

August 20, 2020, 10:45am

Share

Tweet

Snap

"Iwill kill when instructed. I am Satan's little whore,” reads a diary note dated June 6, 2009—five months and two days since Nathan’s wife Kylie borrowed the family station wagon, drove to Bible study and never returned. He can see that it is her handwriting: a familiar, neat scrawl, like a lot of the confessional letters that came into his possession 12 months after his presumed soulmate walked out on him and his son.

“If I disobey I die,” reads another. "I am a bad girl and I deserve this… I'm ugly, I am nothing. I only matter to the cult."

Nathan remembers the afternoon vividly. Kylie, who had struck up a friendship with a small group of fellow Christians in the lower Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, was preparing to head off to one of her increasingly regular women’s Bible study sessions. He was happy for her. Having suffered several brief but severe bouts of postnatal depression following the birth of their then six-year-old son, Liam, it was a relief to see her socialising with what appeared to be a generous and like-minded group of people. She said she’d be home for dinner.

Other notes in Nathan’s collection are written in a hand he doesn’t recognise—most likely scribbled down by various members of the group, he suggests, or possibly one of Kylie’s multiple personalities, of which there are now allegedly hundreds.

Some of the missives appear to have been jotted down during the “counselling sessions” that started taking place at the meetups in the weeks leading up to Kylie's disappearance. Many look as if they’ve been scribbled down by a child—an infantile version of Kylie’s handwriting—and describe hyperviolent scenes of torture and abuse: dogs hanging from trees; babies being decapitated; men having their tongues cut out and their mouths stapled shut and their eyes burned out with flaming sticks.

All of these letters were passed on to Nathan 10 years ago by another man, Wayne, who lost his wife to the same group. “These were lying about the house before my wife left, and I collected them,” Wayne told him at the time. “I can't believe it, but they kept notes on everything.”

The notes Wayne gathered read like dispatches from another realm: a world of angels and demons and Christian mythology, all allegedly operating right under Nathan’s nose, in the leafy suburbs of the lower Mountains. They are a case history of a woman who fell prey to a fanatical religious sect, and a rare window into how good people get sucked into bad cults.

More than that, they are handwritten testimony to a series of events so surreal that, for years, Nathan’s constant refrain was “this is the kind of thing that happens to other people, or in movies, or on television”. He’s long since come to terms with the fact that it was real, and it happened to him.

Until 2009, the lives of Nathan and Kylie Zamprogno were what many people would call unremarkable. Nathan included.

They had just moved to a small town near the foothills of the Blue Mountains: a quiet part of the world known for its charming village communities, its dramatic natural scenery and, as a semi-ironic joke among outsiders, its “cults”. They owned a house, both worked at the same non-denominational Christian school—Nathan in I.T. and Kylie as a receptionist—and drove their 6-year-old son to Kindergarten every morning in a Subaru Forester station wagon. It was, as Nathan tells it, “the good life”.

A ZAMPROGNO FAMILY PHOTO, FROM HAPPIER TIMES.

“What typified our marriage and our family life was how ordinary we were, and how fortunate we felt to have a conventional family,” he tells VICE over video call. Then he delivers a line he’s become fond of over the years. “Horror stories usually start with an ordinary scene, and then, by degrees, turn sinister. And that’s exactly what happened in our case.”

With the clarity of hindsight it’s easy to pinpoint the incremental steps by which sinister forces entered the Zamprogno family’s orbit—but at the time, the sequence of events were deceptively unexceptional. Kylie had started working casual shifts at the school until she was healthy enough to resume her dream job as an emergency nurse at a major Sydney Hospital. The worst of her depression seemed to be behind her. She was making friends, and before long a tight-knit group who had associations with the school board had invited her around to study at their weekly Bible group.

“I kick myself now, because that's when the trouble started,” says Nathan. “No one recruits you to a cult by saying ‘hey, join our group and we'll ruin your life.’ But at the time I just had no idea. So off she went on odd evenings to socialise with this group.”

Gradually these “odd evenings” became more frequent. They ran later. On more than one occasion Nathan recalls sitting up past midnight, waiting for Kylie to respond to his messages. He had started noticing changes in his wife and was worried she was becoming unwell again. More often than not, another woman named Virginnia—the host—would reply: Kylie was undergoing counselling, and would call him in the morning.

On the morning of January 5, 2009, Kylie didn’t call. She didn’t come home, that day or the next, and hasn’t been home since.

With his neatly buttoned shirt and soft expression, Nathan is affable in his appearance. But there is also a hardness to him. He is at once polite and disarmingly candid; confident, but not without a sense of guardedness. He describes himself as a good judge of character, an optimist but also an empiricist, and a reluctant agnostic.

“I’ve seen enough evil, enough religious sanctimony and hypocrisy done in the name of Jesus to last me a lifetime,” he says. “Christians have turned me away from the church.”

In 2010 , Nathan joined the committee of the Cult Information and Family Support group (CIFS), Australia’s leading advocacy network for cult abuse. He counselled people who had lost loved ones to cults, or come out of cults themselves, and who needed to process the experience.

“People respond to cult situations in different ways,” he says. “Some people when they come out of cults withdraw into themselves, while there are other people who feel really angry at the years of their life or the normal relationships that they were robbed of, and they stay good and angry.

“I am in that camp, but I’m odd in the sense that I was never in the cult. I lost a loved one to a cult. And I went on the warpath.”

It wasn’t until more than a year after Kylie left that Nathan found out what had really been happening at the Bible study meetups: when Virginnia’s husband, Wayne, handed him a tranche of notes, scribbles and diabolical ramblings that documented the whole thing.

“They met here,” Wayne told him when the two of them first convened, in the dining room of Wayne’s house. Wayne pointed to a series of smudges above the doors and windows. "Do you see those greasy marks, Nathan? That's where they made little crucifix marks with holy oil. To keep the demons out.”

Wayne went on to explain that the group had been “treating” Kylie, and had diagnosed her with a condition known as Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID—previously Multiple Personality Disorder) where an individual’s psyche splinters into a number of distinct personalities, or “alters”, usually as a coping mechanism for intense childhood trauma. They believed that in Kylie’s case, that trauma happened to be repeated incidents of Satanic ritual abuse.

During her treatment sessions she was encouraged to elicit memories of being horrifically abused by her own family, reciting allegations that, among other things, she was forced to live under the house and was fed like a dog; that she had boiling water poured into her ear; and that she was taken to bushland locations by hooded figures and forced to witness human sacrifice. “All very, very wild claims,” according to Nathan. “Kylie was the eldest of four siblings, and the others reported a completely normal and loving upbringing.”

For Virginnia and the others, though, it made perfect sense: such gratuitous cruelty and abuse, at such a young age, was precisely the kind of thing that typically triggered cases of DID. In their view, Kylie’s mind had fragmented into hundreds of alters as a way of escaping harrowing memories from her past. Some of these alters—going by names like Hope, Joy and Truth—were childish in their disposition, while others—going by names like The Dark One—were considered demonic.

"Some of the alters wanted to hurt her,” Virginnia reported. “They would go and drink bleach, they would try and get her hand in the fire, they would run in front of trucks. So we kept the doors locked to keep her safe."

Behaviours that most people might have interpreted as signs of serious psychological distress were, as far as the group was concerned, evidence of Satanic influence. And beyond locking the doors and shuttering the windows, they believed there was only one remedy for such a thing.

“So Kylie was subjected to exorcism,” says Nathan. “In Australia, in the twenty-first century… She had a genuine mental illness but they were diagnosing her with demons and casting them out.”

It was around this time that Nathan received some disturbing correspondence from Kylie: a suicide note, addressed to their son. Certain scribblings in the diary from around this period make similarly ominous declarations. “I will obey at all costs” reads one. “The only way out is death" reads another.

The last time Nathan saw Kylie in the flesh was half a decade ago. He has no trouble remembering how she looked at the time: “Unwell, and vulnerable. And totally in the thrall of the cult.”

As far as he knows, Kylie never suffered DID before falling in with Virginnia and her crew—although he admits that she was inclined to tell “tall tales” from time to time, usually to curry favour or attention in social situations. Overall, he insists, there was no predisposition that would make her more susceptible to manipulation or religious indoctrination than anyone else. “That’s not the person I married,” he says. “Not at all.”

The implication is that this could happen to anyone: that under a particular set of misfortunes, perfectly unremarkable and ordinary people can, by turns, get sucked into the most unlikely vortexes. But it’s hard to get away from the question: How well can you really know someone? And how much of what appears from the outside to be a process of corruption, manipulation and radicalisation on the part of the so-called abuser, is in fact a conscious and consensual action on the behalf of the so-called victim?

To put it another way: how much agency does a person actually have when they uproot their life, walk out on their family and join a religious sect? In Kylie’s case, Nathan wagers some balanced odds: about fifty-fifty.

“Why is it that anybody gets involved in a cult?” he muses. “Do people get involved in cults because they’re stupid? Well, manifestly not: there are very smart people who fall for cults. So what is it? What’s the characteristic we’re looking for?”

It’s a question Nathan has spent a lot of time thinking about. The answer, he believes, is a particular kind of situational vulnerability in a person. Maybe they’ve moved to a new city and don’t have any friends, or have recently lost a loved one, or had a health scare. Maybe they’re in “a season of their life where they’re searching for answers to bigger questions”. These vulnerabilities, says Nathan, are things that cults are skilled at preying upon.

“I feel for my ex,” he tells me. “You have to understand that Kylie, as well as making some exceptionally poor choices, was unwell. And I will not victimise her further by painting her as the villain in this story; she is a victim, and it’s the members of that cult who I think are the real villains of the story.”

That story—of a wolf in lamb’s clothing luring a vulnerable Church-goer into a pseudo spiritual clique—is neither new nor entirely unique. Having spent several years meeting and speaking with others who had lived through similar experiences, Nathan came to realise that the methods by which his wife was indoctrinated into this group were overwhelmingly commonplace—taken straight from the playbook of How to Recruit Cult Members.

There are a number of techniques that these kinds of groups typically deploy, he explains. First they plant the seed. One or several members from the group will subtly convince an already vulnerable individual that they are special; that they have a unique destiny waiting to be fulfilled; that they’re being held back by the people with whom they associate and that there is another path they could plausibly take to achieve maximal self fulfilment or enlightenment. Often the means of reaching this state of fulfilment are placed just out of reach, prompting the individual to invest ever more into the group—either personally or financially—in order to come closer to attaining satisfaction.

From there the converts are coerced into believing that they should disregard the opinions and advice of others—especially when that advice criticises the particular sect within which they’ve suddenly found themselves. They are weaned off the affections of their families and friends and gradually have their “critical thinking toolkit”—the voice in one’s head that might otherwise raise alarm when something’s not quite right—suppressed.

“The things that are obviously dodgy to you or I, that part of a cult member’s brain has been anaesthetised,” Nathan explains. “And often when people come out of cults, it’s because their critical thinking faculties have woken back up and they realise they’re being abused and they leave.”

That never happened for Kylie. Instead, the group slowly tightened their grip around her, enlisting the help of like-minded fundamentalists to affirm her DID diagnosis and attempting to claim legal guardianship over her. Kylie was eventually deemed disabled in the eyes of the government, and therefore unfit for work. Virginnia is now her carer.

As far as Nathan is concerned, both Kylie and Virginnia became embroiled in a shared delusional disorder, or “folie à deux”—otherwise known as a “madness for two”. It was in Virginnia’s interest to keep Kylie sick, he says, possibly even exacerbating her symptoms so that she could adopt the role of a carer.

There’s a name for this. Clinicians call it Munchausen By Proxy when a caregiver fabricates, exaggerates or causes an illness or injury for a person under their care—usually for reasons unknown. The behavioural condition is broadly considered to be a form of abuse. But Nathan later discovered that, in Kylie and Virginnia’s case, there was also a financial interest to the arrangement.

“Neither, to my knowledge, have drawn a cent in wages for the last decade because they get government benefits,” he says. “One is a disabled person in need of care, the other is a full-time carer, and they get by on that income.”

It speaks to what might be the most obvious question in this whole ordeal. For all the pain and suffering they inflicted, what did the sect get out of it?

“The question that's often asked of cults or cult leaders is are they mad, or are they bad?” Nathan explains. “In other words: are they deceitful, and they know that this is all a scam; or are they deluded, and they actually believe that they are a Faithful Remnant of the church and that mainstream religious denominations are all being secretly controlled by devil worshippers who, at various times, gather in covens in remote locations to commit human sacrifice?”

This group, he’s concluded, falls into the latter.

“They actually believe these things. So what’s in it for them is ratification; a vindication of their particular spiritual theological belief. They believe they're engaged in spiritual warfare with a coven of Satanists operating up and down the Blue Mountains. And you can point and laugh at that, but you get to a point where you think: this isn’t just ridiculous, it's dangerous. People are being hurt.”

It is for this reason that Nathan and CIFS have been advocating for the Australian government to clamp down on the predations of cults by tightening restrictions around behaviours, as opposed to beliefs.

“You can believe the moon is made out of cheese if you want to,” he explains, “but if you start abusing people psychologically, and perverting their psychological care, and draining their bank accounts, and weaning them off the affections of their families, that's a violent act. And there should be some consequence for it.”

As it turns out, there isn’t. Although Australian law clearly prohibits acts of kidnapping, fraud, and holding a person against their will, there are no laws against brainwashing, scaremongering, or coercion. Nathan and CIFS contend that these things constitute forms of psychological abuse—but there is no clear legislative definition of what “psychological abuse” actually looks like. And while there are a number of result-based offences that make it a crime to have caused psychological harm, they're untested, hard to prove, and harder still to nail down.

“To date, not one person has been prosecuted in Australia for actually causing psychological harm to another person under the various result-based offences,” Paul McGorrery, a PhD Candidate in Criminal Law at Victoria’s Deakin University, told VICE over email. “Stalking laws, to my knowledge, have never been operationalised to target psychological abuse as you describe it, and we have no laws that specifically criminalise psychological abuse.”

Meaning, in short, that the best thing Australian law has to protect people against the predations of cults is a motley assortment of straw men and paper tigers.

This is what Nathan—the self-proclaimed optimist, empiricist, and reluctant agnostic—is fighting for in his new life as a politician. Nathan was elected a Councillor on Hawkesbury City Council in 2016 and stood for Liberal preselection for the NSW State seat of Hawkesbury in 2018. Now he wants governments to adopt meaningful laws around where religious freedoms start and end, and to actually prosecute people who inflict psychological harm.

“Nothing does more damage to mainstream religious denominations who do good work in the community than bad apples who poison the well,” he explains. He also wants to see bodies like the Australian Charities and Not for Profits Commission and the Tax Office to apply a more stringent Public Benefit test, and the establishment of a formal body that examines radical religious groups with more scrutiny.

Reforms like these have become a quest in his public life—even if he’s long since given up the fight to rescue his own wife from the perils of religious fundamentalism.

“I stopped fighting for Kylie when, three or four years down the track, I gave myself permission to be happy with the shape of my life,” he says. “In the immediate aftermath of her disappearance, I was fervent in what I characterised as rescuing my wife from a diabolical situation. But by degrees I came to realise that, to quote Voltaire, ‘you can’t rescue somebody that loves their chains’. Eventually you have to abandon people to their fate.”

You can see the Blue Mountains from where Nathan lives with his now-18-year-old son, Liam, in the Hawkesbury region of western Sydney. Liam is in Year 12 now, Nathan having raised him as a single parent with the help of his own family as well as Kylie’s. He’s done well in life, he admits. He’s happy.

Eleven-and-a-half years since Kylie backed down the driveway for the very last time, Nathan has reclaimed some form of the pleasantly conventional existence he once held so dear—albeit, with a few caveats. He’s learned that an ordinary life isn’t insulated against extraordinary events; that faith is not the same as kindness or virtue; and that devotion, particularly extreme devotion, can be co-opted as a force for both good and evil.

He has come to these lessons the hard way, through extreme and improbable circumstances. But anyone who finds his story unimaginable is missing the point.

“If you look at the worst examples of cults—Jonestown, Heaven's Gate, Waco and so forth—you'd have to ask: what brings people to that fever pitch, where their beliefs become delusional?” he says. “And it's a very uncomfortable thing for us to grapple with as a society that people—ordinary people—can be induced to do that. It's the same moral debate that asks why good people permitted Nazis to feed people to the gas chambers.

“Ordinary people can do very bad things,” he concludes. “And as Christopher Hitchens always said, if you want good people to do very bad things then what you need is religion. Religion is the only force in the world that can cause good, mild, boring people to commit atrocities.”

Virginia and her sistren have since disappeared back into the woodwork. Nathan suspects his long campaign of exposure has all but destroyed the group’s standing in the community, and forced them to go underground. But he also worries that there are more atrocities to come.

“One day, this group will so badly abuse somebody—whether it’s Kylie or somebody else—that someone will come to harm or die,” he portends. “And then if there’s a coronial inquest, the information given to me makes them incredibly culpable.”

As for his current feelings toward Kylie, the word Nathan lands on is pity—“pity in the same way someone might feel pity for a person who has been dealt a very bad hand in life, or made poor life choices, and is now reaping the consequences”. Pity and nothing else.

Liam, he says, feels utterly apathetic towards his mother, who is by now a dimming memory. It wasn’t until he was in his late teens that he asked to know the truth about everything that had happened. And Nathan, having protected him from it his whole life, finally handed him the source material.

“He went through all of the articles,” Nathan says. “And from his perspective, religious people stole his mother. So now he wants nothing to do with organised religion—because if that’s religion, you can have it.”

They’ve both long since moved on with their lives. But that doesn’t mean Nathan’s completely closed the book.

“I’ve characterised this as a missing persons case, in the sense that if a person dies you’ve got closure, but if a person goes missing then you lack even that closure,” he explains. “Somebody is out there with that person’s face, but not even going by that person’s name anymore. A shell of the person they used to be. A walking, human tragedy.

“I don’t want it to get to a coronial inquest before the truth is known,” he continues, “but I’ve also reconciled myself over the years to having many questions that I may never know the answers to. Why did these people do what they did? Why did Kylie choose to do what she did? Where will this all end? I do not know.”

If you or a loved one has experienced a situation like this, resources are available to help.

The Cult Information and Family Support Network and the Australian False Memory Association are Australian voluntary organisations. Immediate counselling help can be found at Lifeline, and Nathan invites contact through his own website.

Gavin Butler is a senior reporter for Vice Asia-Pacific. Follow him on Twitter

读完这篇文章后心情如何?